Integrity is important to all components of teaching and learning. One of the most critical factors is determining fact vs opinion, especially when it comes to “fake news” and basing analysis on fact. In this post, Lisa Macdonald, award-winning faculty at an elementary school in the United States, shares a lesson plan revolving around “Fact vs Opinion” that can be shared with students as early as primary school. --Turnitin

Things can get heated in a classroom. Which basketball team is best? K pop or hip hop? And of course, the deeply divisive: Spiderman or Black Panther? Often, the first instinct of a teacher is to squash these perpetual battles as quickly as possible with a hollow, “Agree to disagree” or the classic “This isn't a conversation for the classroom.” There are, after all, pacing guides to which we adhere.

But as a teacher throughout the years, I wondered if these arguments were missed opportunities to develop my students’ critical thinking skills. These were topics about which the students cared deeply and to which they connected naturally. The passion was there, but the skills to craft a rich and compelling discussion were what was needed. Too often the “winners” of the aforementioned arguments were the loudest, most outgoing students or those who were the most popular amongst their peers. It was frustrating to watch and became even more concerning when students latched on to misinformation because it came from an appealing source such as YouTube. The consequences of not addressing misinformation and missing the opportunity to teach critical thinking are many. And it’s important to address the difference between fact and opinion early on.

With this in mind, there are three elements critical to understanding the difference between fact and opinion:

- Understanding how facts are different from opinions

- Recognizing expert information and sources

- Using empathy to understand opposite opinions and convince others to agree with you

These elements are important to both a student’s academic and personal life journey; and teachers play a critical part in ensuring that students have the tools to navigate truths.

What constitutes a fact?For second grade (and quite honestly, this is relevant for secondary and higher education as well) we simplify it: Facts can be proven by more than one person and remain true regardless of how a person feels about it.

It helps to present many examples and talk about this concept directly to learners so they can move past the idea that “If I agree with it, it’s a fact.” I present something like “Cats are carnivores,” and compare it to an opinion like “Cats are the best pets.” If someone can feel differently about your statement, it is likely an opinion.

And make sure to choose exemplar facts carefully. Funny story: I once said that cats were covered in fur. I was then treated to a 10-minute lecture by my very excited student about her hairless cat, its bathing routines, and favorite skin lotions. It was a great moment to capitalize on for a discussion of outliers, but best to avoid such pitfalls if you're trying to stay on track.

Who should be considered an expert and why?Someone being popular, powerful, or pretty doesn't make them an expert. Is that 12th grader on the bus really an expert? Chances are, no, they just feel powerful. I teach my students that experts spend years reading, learning, and experiencing the things they are passionate about in order to be considered experts. They are usually evaluated by other experts in their same field, ensuring multiple fact checks.

Again, to simplify it for elementary, we discuss how people who declare themselves experts without prior experiences are “cheating” or passing rumors and are likely trying to convince you with their opinion and not facts. Their reason for doing this is usually monetary. It is always a mind-expanding experience for my students when they discover that many things on YouTube, while live action, are intentionally entertaining opinions designed to get your money.

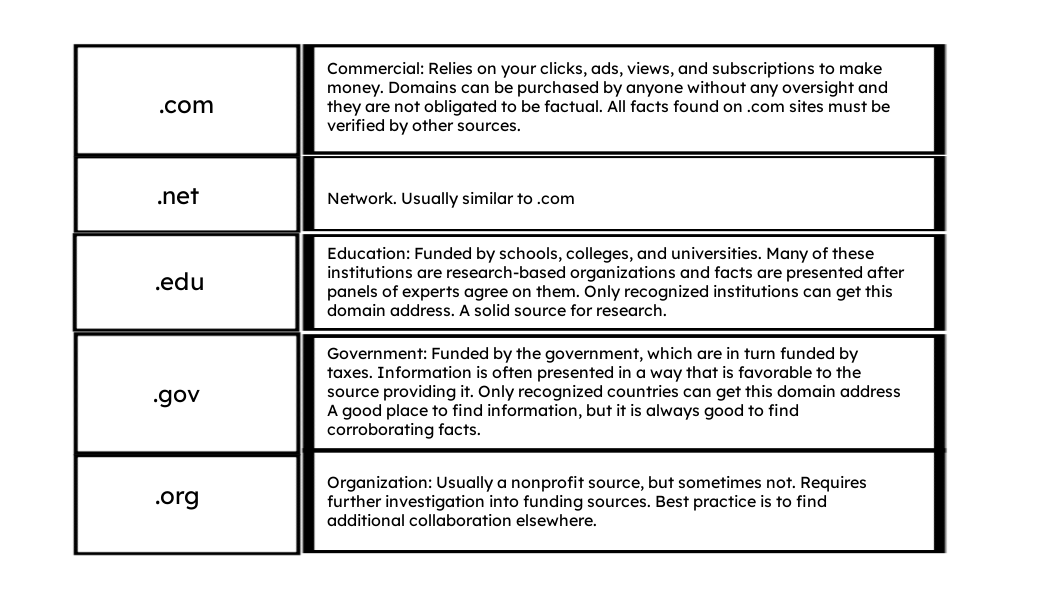

Our anchor question for this work is: Who is providing your facts and how do they get funded? Since most of our research is online, I begin by teaching my students about web address domain abbreviations. It may surprise you that even second graders love these lessons. They feel like they have been let in on a major adult secret and appreciate having the tools to better understand how the internet works. The following is a table I created with my students after examining several examples of each domain type:

The shift in mindset away from being the most “right” to instead understanding others and convincing them to agree with you is the ultimate goal of this work. Bullying opinions that are different from ours seems to be an almost universal approach in the beginning. Empathy is the key.

Working to understand why someone would feel differently than you about an issue helps students build their strongest argument. It usually goes as follows: A student wants to convince people that pepperoni pizza is better than cheese pizza. When asked why someone might enjoy plain cheese pizza over pepperoni, their face crinkles. Their first response is almost always self-centered. “Pepperoni is good! Cheese is for babies!” they exclaim.

“Why don’t some people like it?” I prompt.

With dawning awareness they say something like, “It’s spicy. Some people don’t like spicy food.”

Now the fun part. “What would you say to convince them to change their position?”

Their eyes light up realizing they have power. “When they grow up there will be lots of spicy food. You should try to get used to it. Also, you can put pepperoni on your pizza and if you don’t like it you can peel it off!”

Opinions rarely sway the opposition. Facts with which a person can connect are much more likely to persuade change. These principles inform critical thinking and help students understand the importance of facts in persuasive writing, for instance.

My students use their newfound skills to produce letters and media reviews. Some have written to principals and politicians. Others write to their parents lobbying for increased screen time, allowances, and family pets. Many students enjoy submitting reviews of their favorite books, movies, and games. This is usually the most popular unit I teach because of its authentic connection to and application in my students' real lives.

We adults have witnessed firsthand the devastating consequences of living in a world where facts are now considered disposable if they do not conform to a personal opinion. We have watched as opinions steeped in flawed logic become public policy. Vilifying those who disagree with you is the norm. Too often I’ve felt paralyzed by feelings of helplessness in the light of these cultural shifts. My solution is to bring to my students the skills they will need to confidently interpret the information that bombards them. By teaching them to understand the difference between fact and opinion, my goal is to teach them how to think, not what to think. In this way, I’m doing my part to combat the misinformation circus.

In closing, I bring you an outline of this fact vs opinion lesson series. I hope it helps you support your students, whether primary or secondary or higher education, in their learning journey.